September 2015

Oliver Mtukudzi and

The Black Spirits

Oliver Mtukudzi and the Black Spirits

Flamingo Cantina

Austin, Teaxs

“Hello Austin! We are coming from Zimbabwe. And if you have never been to Zimbabwe, we’re here to take you to Zimbabwe.” So declared Oliver Mtukudzi at a crowded Friday night performance at Sixth Street’s Flamingo Cantina. Zimbabwe’s national treasure and the most successful African recording artist in North America, Mtukudzi and his band the Black Spirits did indeed transport their audience to a place where “music is like food” and “you don’t get to sing a song if you have nothing to say.”

Mtukudzi had a fair amount to say: where he comes from, people use music “to talk about our pain, our frustrations, our joys.” Despite the struggles his lyrics – a mixture of Shona, Ndebele and English – communicate, his unique tuku music style has an upbeat vibe. A little bit of Afropop, mbira, mbaqanga, jit, and Korekore drumming combined with husky, almost soul-rock vocals reminiscent of Otis Redding make for a highly energetic winning combo, invoking the possibility of singing all one’s troubles away. “Hear me Lord, I’m feeling low” sounds less like an agonized cry than a hopeful prayer, reminding the listener that pain need not couple with overwhelming despair.

Mtukudzi had a fair amount to say: where he comes from, people use music “to talk about our pain, our frustrations, our joys.” Despite the struggles his lyrics – a mixture of Shona, Ndebele and English – communicate, his unique tuku music style has an upbeat vibe. A little bit of Afropop, mbira, mbaqanga, jit, and Korekore drumming combined with husky, almost soul-rock vocals reminiscent of Otis Redding make for a highly energetic winning combo, invoking the possibility of singing all one’s troubles away. “Hear me Lord, I’m feeling low” sounds less like an agonized cry than a hopeful prayer, reminding the listener that pain need not couple with overwhelming despair.

The band’s synergy shone through as they performed a number of low-key synchronized dances together. Mtukudzi snuck in a solo dance during a folksy guitar riff, calling to mind the image of a bird getting off the ground, reaching towards the sky. The rhythms of his beats were enough to stir even the saddest show-goer to dance, and the easy blending of language lent a certain universality – indeed, an audience of all races and ages turned out to soar on the melody of pain-turned-art. Multilingualism is not required to experience the rejuvenating, utterly hopeful feel of Mtukudzi’s songcraft.

by Nori Hubert

Flamingo Cantina

Austin, Teaxs

“Hello Austin! We are coming from Zimbabwe. And if you have never been to Zimbabwe, we’re here to take you to Zimbabwe.” So declared Oliver Mtukudzi at a crowded Friday night performance at Sixth Street’s Flamingo Cantina. Zimbabwe’s national treasure and the most successful African recording artist in North America, Mtukudzi and his band the Black Spirits did indeed transport their audience to a place where “music is like food” and “you don’t get to sing a song if you have nothing to say.”

The band’s synergy shone through as they performed a number of low-key synchronized dances together. Mtukudzi snuck in a solo dance during a folksy guitar riff, calling to mind the image of a bird getting off the ground, reaching towards the sky. The rhythms of his beats were enough to stir even the saddest show-goer to dance, and the easy blending of language lent a certain universality – indeed, an audience of all races and ages turned out to soar on the melody of pain-turned-art. Multilingualism is not required to experience the rejuvenating, utterly hopeful feel of Mtukudzi’s songcraft.

by Nori Hubert

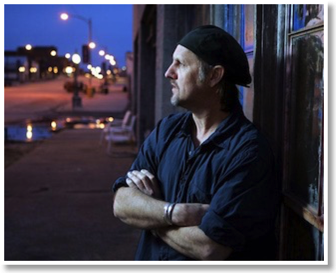

Jimmy LaFave

Jimmy LaFave

Strange Brew

Austin, Texas

Audience members were quietly sipping their beers, or quickly devouring their Strange Brew victuals with nary a word in between. Most attendees simply stared ahead with solemnity as they watched musician Jimmy LaFave and his band prepare their equipment with quiet devotion to the lighted stage; indeed, LaFave’s own dress, a blacked out shirt, pants, boots and backwards beret combo, seemed to add to the severity of the scene. However, with nothing more than his casual and easygoing demeanor, LaFave all but dispelled this solemnity immediately with the onset of his show; amiably conversing with members of the front row, or even commenting on the grim aspects of the darkening Strange Brew venue.

Audience members were quietly sipping their beers, or quickly devouring their Strange Brew victuals with nary a word in between. Most attendees simply stared ahead with solemnity as they watched musician Jimmy LaFave and his band prepare their equipment with quiet devotion to the lighted stage; indeed, LaFave’s own dress, a blacked out shirt, pants, boots and backwards beret combo, seemed to add to the severity of the scene. However, with nothing more than his casual and easygoing demeanor, LaFave all but dispelled this solemnity immediately with the onset of his show; amiably conversing with members of the front row, or even commenting on the grim aspects of the darkening Strange Brew venue.

It was LaFave’s friendliness and laidback demeanor that seemed to capture the essence of LaFave’s two biggest influences, Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan. If early folk music was built on the intimacy and grassroots relationships that sprung from such a closeness between musician and fan, LaFave certainly seemed to adhere to that relationship with gentle passion. From speaking with members of the crowd on a first name basis, to playing a request for a couple who was celebrating their anniversary that night, to gently teasing his keyboardist Bryan Peterson for leaving his group to head to Europe for the summer, or to anecdotally yet affectionately commenting on his appreciation for his drummer Bobby Kallus’ restored good health and return to performing, LaFave’s passion and appreciation for such a relationship seemed to be almost palpable for all those who could see.

On stage, LaFave seemed to run through the gamut of his musical influences; while playing songs old and new, such as the hit “Only One Angel” to new cuts from his forthcoming album The Night Tribe. LaFave also played a variety of covers, ranging from a country-rock rendition of Jackson Brown’s “These Days,” to a pitch-perfect cover of Dylan’s “Queen Jane Approximately,” one of those aforementioned cuts from his new album, to his rousing and spirited closing cover of Creedence Clearwater Revivals’s “Have You Ever Seen the Rain,” his self-described “sing-along song,” which encapsulated LaFave’s folk pathos when he enthusiastically called out to both sexes of the crowd to sing out the chorus separately. Truly, the sincerity of LaFave’s performance and the genuineness that exuded from his persona on stage was hard to resist; according to Mary Jane Fross, who, with her husband Chuck, had travelled all the way from San Francisco to celebrate their 40th anniversary with this show, stated that it was “his sincerity, and the articulateness of his lyrics” that endeared LaFave so much to her and her husband, and she added, “was hard to find in musicians today.” It would seem from the smiles in the crowd, they too agreed.

by Andrew Chauvin

Strange Brew

Austin, Texas

It was LaFave’s friendliness and laidback demeanor that seemed to capture the essence of LaFave’s two biggest influences, Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan. If early folk music was built on the intimacy and grassroots relationships that sprung from such a closeness between musician and fan, LaFave certainly seemed to adhere to that relationship with gentle passion. From speaking with members of the crowd on a first name basis, to playing a request for a couple who was celebrating their anniversary that night, to gently teasing his keyboardist Bryan Peterson for leaving his group to head to Europe for the summer, or to anecdotally yet affectionately commenting on his appreciation for his drummer Bobby Kallus’ restored good health and return to performing, LaFave’s passion and appreciation for such a relationship seemed to be almost palpable for all those who could see.

On stage, LaFave seemed to run through the gamut of his musical influences; while playing songs old and new, such as the hit “Only One Angel” to new cuts from his forthcoming album The Night Tribe. LaFave also played a variety of covers, ranging from a country-rock rendition of Jackson Brown’s “These Days,” to a pitch-perfect cover of Dylan’s “Queen Jane Approximately,” one of those aforementioned cuts from his new album, to his rousing and spirited closing cover of Creedence Clearwater Revivals’s “Have You Ever Seen the Rain,” his self-described “sing-along song,” which encapsulated LaFave’s folk pathos when he enthusiastically called out to both sexes of the crowd to sing out the chorus separately. Truly, the sincerity of LaFave’s performance and the genuineness that exuded from his persona on stage was hard to resist; according to Mary Jane Fross, who, with her husband Chuck, had travelled all the way from San Francisco to celebrate their 40th anniversary with this show, stated that it was “his sincerity, and the articulateness of his lyrics” that endeared LaFave so much to her and her husband, and she added, “was hard to find in musicians today.” It would seem from the smiles in the crowd, they too agreed.

by Andrew Chauvin

Junior Brown

Junior Brown

Stubb’s

Austin, Texas

The crowd erupted in applause and whistles as Junior Brown took the stage recently carrying his trademark guit-steel guitar, and dressed in his trademark suit with white cowboy hat.

Brown was at home on the stage, interacting with his fans and playing the crowd with a smile on his face. He played his guitar with fingers flying up and down the neck to match the lively nature of his songs. Most songs were separated with an intense solo from Brown.

When he sang “Lifeguard Larry,” the crowd filled with laughter. The song, about a lifeguard who gives mouth to mouth to all the pretty girls, was a favorite with the fans on Sunday night. Nothing stood up to “Highway Patrol,” however. The crowd was filled with screams and hollers when he broke into this one. Everyone knew the words and belted them at the top of their lungs with Brown. The ladies swung their hips, and the men tried to suppress their excitement into casual head bobbing.

Brown’s show seemed to be one of traditional country music, and the audience with their nods and smiles seemed to enjoy his performance.

by Caroline LaMotta

Stubb’s

Austin, Texas

The crowd erupted in applause and whistles as Junior Brown took the stage recently carrying his trademark guit-steel guitar, and dressed in his trademark suit with white cowboy hat.

Brown was at home on the stage, interacting with his fans and playing the crowd with a smile on his face. He played his guitar with fingers flying up and down the neck to match the lively nature of his songs. Most songs were separated with an intense solo from Brown.

When he sang “Lifeguard Larry,” the crowd filled with laughter. The song, about a lifeguard who gives mouth to mouth to all the pretty girls, was a favorite with the fans on Sunday night. Nothing stood up to “Highway Patrol,” however. The crowd was filled with screams and hollers when he broke into this one. Everyone knew the words and belted them at the top of their lungs with Brown. The ladies swung their hips, and the men tried to suppress their excitement into casual head bobbing.

Brown’s show seemed to be one of traditional country music, and the audience with their nods and smiles seemed to enjoy his performance.

by Caroline LaMotta